Introduction

Errors in JavaScript are often treated as something that happens to you — something you catch, log, or turn into an HTTP response.

That understanding is already broken.

Before an error is caught, handled, retried, logged, or shown to a user, it is created. And how an error is created determines how useful it will be everywhere else in the system.

This post focuses only on that foundation.

- Not on try/catch.

- Not on HTTP status codes.

- Not on retries or fallbacks.

Just the Error object itself:

- what it really is

- what it contains

- why it exists

- and what it is not

Once you understand Error as a data structure — not a control-flow mechanism — many of the common confusions around error handling simply disappear.

How an Error is represented

In JavaScript, Errors are represented using the Error class. Error is just a class, just like any other class. There is nothing magical or runtime-breaking about it.

const err = new Error("Something went wrong");When you create an object of the Error class:

- nothing crashes

- nothing stops executing

- you just created an object

This tells you something important:

Creating an Error is just like creating any other object in JavaScript.

Think of an Error like:

A standardized container for describing failure and where it came from

Why use Error at all?

If it is just a class, why use it instead of using a string, a plain data type, or maybe a custom class? The reason is that the Error class gives you additional properties that are helpful for dealing with failures:

- structure

- stack trace

- type information

- tooling support (logs, debuggers, monitoring)

So the real purpose of Error is Observability and propagation, not control flow.

Since an Error is just an object, the following is completely valid:

const err = new Error("Oops");

err.context = { userId: 42, retryable: true };Errors are designed to carry context and meaning across layers, so use them intentionally to attach meaning wherever applicable across boundaries. If boundaries and layers are confusing, you can read the post about boundaries and layers in software.

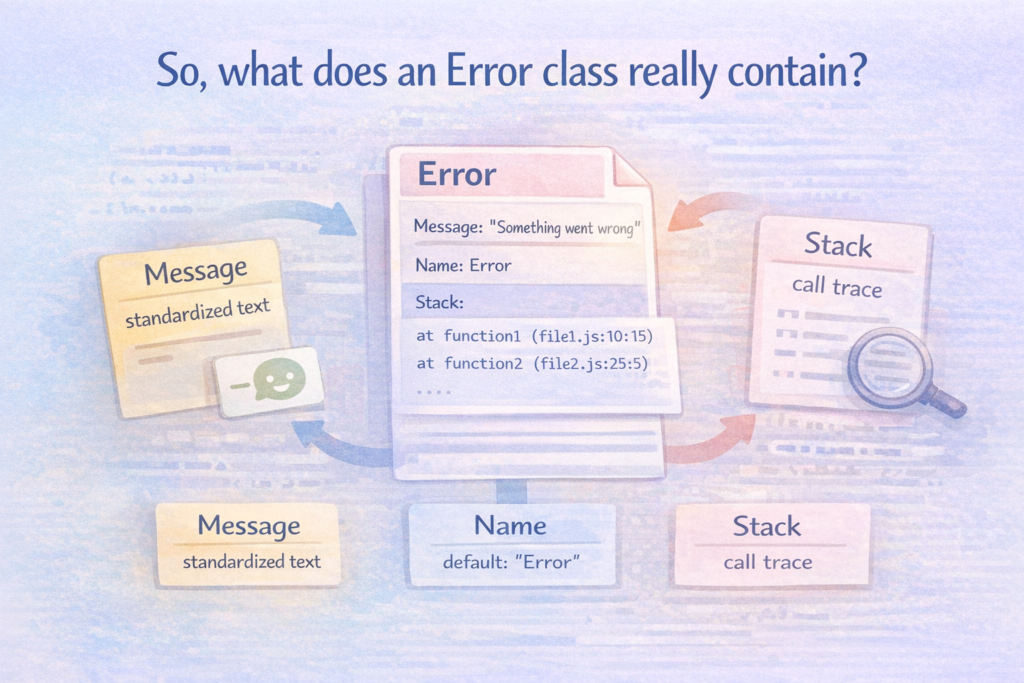

So, what does an Error class really contain?

An Error object typically contains

- message is standardized

- name exists by default

- stack is non-standard but universally implemented

Note that these fields are conventional, and not enforced. Also note that while message and name are part of the standard Error object, stack is not formally standardized. However, stack is supported by all major JavaScript engines.

Error stack is a “string” that contains:

- the error message

- the call stack (where the error was created)

Note that the stack is captured when an Error is created, not when it is thrown. This is why, where you create an Error matters.

Are there any other Error classes in JavaScript?

JavaScript already provides several built-in error types with semantic meaning:

- TypeError

- ReferenceError

- SyntaxError

- RangeError

- URIError

- AggregateError

These are not different mechanisms — they are different categories of failure.

Can you create custom Error Classes?

Yes, you can extend the base Error class to create your own error types.

When doing so, focus on:

- extending Error

- calling super

- preserving stack trace

- meaningful naming

- attaching metadata safely

Avoid:

- HTTP concerns

- status codes

- retry behavior

Custom errors should describe what went wrong, not what to do about it.

For example:

class AppException extends Error {

constructor(

message,

{ metadata = undefined, context = undefined, cause = undefined } = {}

) {

super(message);

this.name = this.constructor.name;

if (metadata) this.metadata = metadata;

if (context) this.context = context;

if (cause) this.cause = cause;

}

}What an Error object is not

Errors are not about HTTP, APIs, or user experience. Error does not mean:

- HTTP 500

- toast message

- retry logic

- user-facing failure

An error simply means:

Something went wrong in this layer, and I want to propagate context upward.

Think of Error as:

A typed envelope that carries failure information, origin, and context across boundaries

Summary

At this point, we’ve only done one thing: understood what an Error object actually is. We haven’t:

- thrown anything

- caught anything

- decided what should happen next

And that separation is intentional.

An Error is about describing failure and preserving context, nothing more. Decisions about retries, user messages, logging, or HTTP responses belong to other layers — and other conversations.

In the next step, the question becomes:

- Where should errors be created?

- Where should they be caught?

- How do they move across system layers and async boundaries without losing meaning?

But none of that works unless the Error itself is well-formed.

Now you know what that foundation looks like.

Leave a Reply