Who is it for?

This post is for anyone who wants to:

- Feel they “know” Errors, but haven’t formed a clear mental model

- Demystify the difference between Errors and Exceptions

- Become better programmers by thinking about failure explicitly

- Understand why handling and propagating Errors is a design decision, not just syntax

Who this is not for

This post intentionally avoids language-specific syntax and code examples. If you are looking for language-specific Error-handling mechanisms and concepts, they may be covered in separate posts.

What really is an Error?

What does Error really mean? In layman’s terms, an Error usually means that something went wrong. However, what constitutes an Error can vary significantly depending on your level of programming expertise. Simply put, an Error is a state(situation) in which the system cannot proceed as intended. Let’s take an example.

You find yourself making breakfast and, while making an omelette, you can’t find tomatoes. You don’t know how to make an omelette without tomatoes. This is an unexpected (invalid) state and, in programming terms, an Error. Now that you’re in this situation, what do you do? You might choose one of the following options:

- Don’t make an omelette and make pasta instead

- Avoid making breakfast altogether and order food

- Ask someone else for help because you don’t know how to proceed

When a system enters an invalid state (an Error), note two important things:

- You need to make a decision.

- Second, the process must either continue via an alternate path or be abandoned entirely.

An Error occurred, what now?

In essence, there are only two options when an Error occurs:

- You handle the situation yourself (by continuing along an alternate path)

- You transfer the responsibility (and control) to someone else

Transferring responsibility means saying: “I don’t know how to continue from here.”

In programming, if you do not explicitly make this decision, the responsibility is passed to the runtime by default. The runtime then applies its default failure behavior – which usually means terminating the program. Hence, it is very important to handle all your errors at some point, or let your program crash.

I can’t handle the error, you take care of it (Exception)

An Exception is a shift in the control flow.

When a system encounters an Error but does not know how to handle it at the current level, it needs a way to transfer control to someone else who might be able to decide what to do next. This transfer of control is what we call an Exception.

Note that, An Exception does not solve the problem. It simply signals that normal execution cannot continue at this level and that a decision must be made elsewhere.

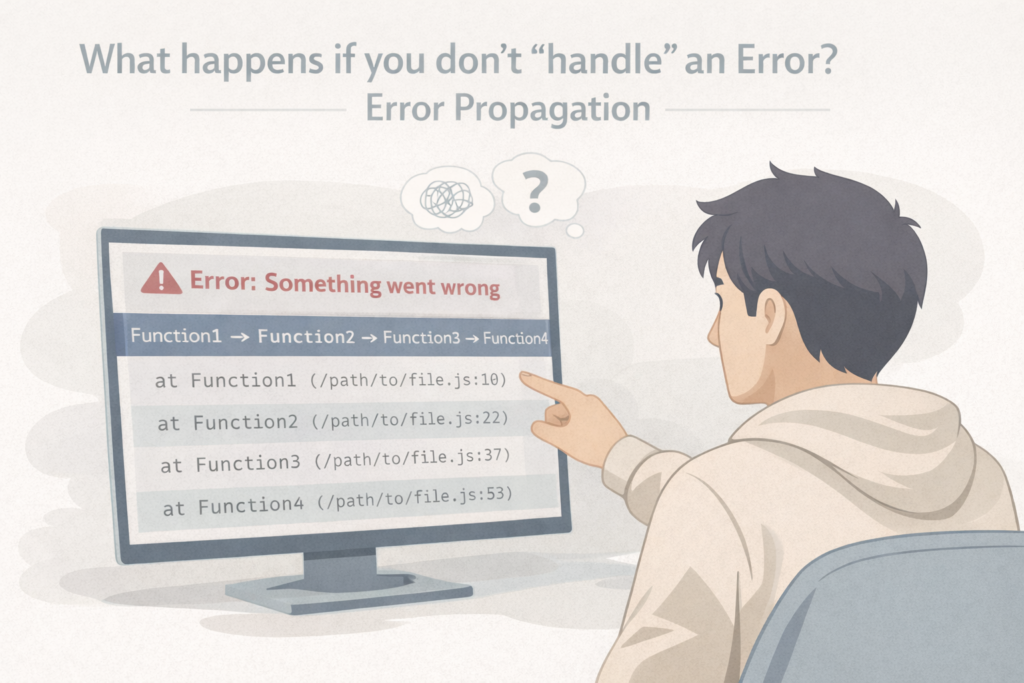

What happens if you don’t “handle” an Error – Error Propagation

As we saw earlier, an Error needs to be handled explicitly or delegated, or it will crash the system down the line.

When you don’t know how to handle an Error, it is usually propagated to the function, service, or caller of that operation. This propagation happens either explicitly via an Exception, or implicitly via the runtime’s default control flow. At each boundary, the service must decide either to handle the Error state, or propagate it back to the caller. This process is also known as “bubbling an Error”. This is possible till the Error state reaches the runtime.

In most systems, the runtime provides a final boundary where Errors that you didn’t handle can be handled. If the Error is still not handled at this boundary, the runtime will eventually terminate the program.

Why this matters

Error handling is not about syntax or language features. It is about deciding where responsibility lives in a system. Once this decision is explicit, the technical mechanisms used to implement it become much easier to reason about.

Leave a Reply